updated 4:49 AM EDT, Sat September 21, 2013

Leon Panetta, the former defense secretary, called the suicide rate among service members an epidemic.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- The data the suicide rate is based on are incomplete

- Examples of uncounted: "suicide by cop," by overdoses and by vehicle crashes

- "There's probably a tidal wave of suicides coming"

- VA makes appeal for more uniform reporting of suicide data

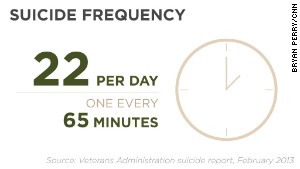

The figure, released by the Department of Veterans Affairs

in February, is based on the agency's own data and numbers reported by

21 states from 1999 through 2011. Those states represent about 40% of

the U.S. population. The other states, including the two largest

(California and Texas) and the fifth-largest (Illinois), did not make

data available.

Who wasn't counted?

People like Levi Derby,

who hanged himself in his grandfather's garage in Illinois on April 5,

2007. He was haunted, says his mother, Judy Caspar, by an Afghan child's

death. He had handed the girl a bottle of water, and when she came

forward to take it, she stepped on a land mine.

When Derby returned home,

he locked himself in a motel room for days. Caspar saw a vacant stare

in her son's eyes. A while later, Derby was called up for a tour of

Iraq. He didn't want to kill again. He went AWOL and finally agreed to a

dishonorable discharge.

Derby was not in the VA system, and Illinois did not send in data on veteran suicides to the VA.

Experts have no doubt

that people are being missed in the national counting of veteran

suicides. Luana Ritch, the veterans and military families coordinator in

Nevada, helped publish an extensive report on that state's veteran

suicides.

Part of the problem, she

says, is that there is no uniform reporting system for deaths in

America. It's usually up to a funeral director or a coroner to enter

veteran status and suicide on a death certificate. Veteran status is a

single question on the death report, and there is no verification of it

from the Defense Department or the VA.

"Birth and death

certificates are only as good as the information that is entered," Ritch

says. "There is underreporting. How much, I don't know."

Who else might not be counted?

A homeless person who

has no one who can vouch that he or she is a veteran, or others whose

families don't want to divulge a suicide because of the stigma

associated with mental illness; they may pressure a state coroner to not

list the death as suicide

If a veteran

intentionally crashes a car or dies of a drug overdose and leaves no

note, that death may not be counted as suicide.

An investigation by the Austin American-Statesman newspaper last

year revealed an alarmingly high percentage of veterans who died in

this manner in Texas, a state that did not send in data for the VA

report.

"It's very hard to capture that information," says Barbara van Dahlen, a psychologist who founded Give an Hour, a nonprofit group that pairs volunteer mental-health professionals with combat veterans.

Nikkolas Lookabill had

been home about four months from Iraq when he was shot to death by

police in Vancouver, Washington, in September 2010. The prosecutor's

office said Lookabill told officers "he wanted them to shoot him." The

case is one of many considered "suicide by cop" and not counted in

suicide data.

Carri Leigh Goodwin

enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2007. She said she was raped by a fellow

Marine at Camp Pendleton and eventually was forced out of the Corps

with a personality disorder diagnosis. She did not tell her family that

she was raped or that she had thought about suicide. She also did not

tell them she was taking Zoloft, a drug prescribed for anxiety.

Her father, Gary Noling,

noticed that Goodwin was drinking heavily when she returned home. Five

days later, she went drinking with her sister, who left her intoxicated

in a parked car. The Zoloft interacted with the alcohol, and she died in

the back seat of the car. Her blood alcohol content was six times the

legal limit.

Police charged her

sister and a friend in Goodwin's death for furnishing alcohol to an

underaged woman: Goodwin was 20. Noling says his daughter intended to

drink herself to death. Later, Noling went through Goodwin's journals

and learned about her rape and suicidal thoughts.

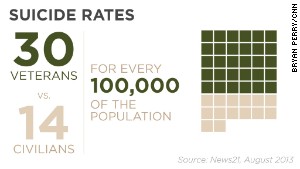

A recent analysis by News21,

an investigative multimedia program for journalism students, found that

the annual suicide rate among veterans is about 30 for every 100,000 of

the population, compared with the civilian rate of 14 per 100,000. The

analysis of records from 48 states found that the suicide rate for

veterans increased an average of 2.6% a year from 2005 to 2011 -- more

than double the rate of increase for civilian suicide.

Nearly one in five

suicides nationally is a veteran, even though veterans make up about 10%

of the U.S. population, the News21 analysis found.

The authors of the VA

study, Janet Kemp and Robert Bossarte, included many cautions about the

interpretation of their data, though they stand by the reliability of

their findings. Bossarte said there was a consistency in the samples

that allowed them to comfortably project the national figure of 22.

But more than 34,000

suicides from the 21 states that reported data to the VA were discarded

because the state death records failed to indicate whether the deceased

was a veteran. That's 23% of the recorded suicides from those states. So

the study looked at 77% of the recorded suicides in 40% of the U.S.

population.

The VA report itself

acknowledged "significant limitations" of the available data and

identified flaws in its report. "The ability of death certificates to

fully capture female veterans was particularly low; only 67% of true

female veterans were identified. Younger or unmarried veterans and those

with lower levels of education were also more likely to be missed on

the death certificate."

"We think that all

suicides are underreported. There is uncertainty in the check box," says

Steve Elkins, the state registrar in Minnesota, which has one of the

best suicide data recording systems in the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment